November 20, 2005

Dear Friends & Family:

My time in Botswana is coming to a close soon. The past 2 weeks have been busy, with busy weeks in the hospital and weekends exploring the wildlife and landscapes of Botswana and nearby.

Work at the hospital continues to be intense, with many sick patients, deaths of some of our patients (many younger than us—young doctors in our 20s and 30s hate to see patients die younger than us—but then doesn’t everyone?), but also with some nice saves. One woman I had feared would just get worse sat up on Tuesday and said, “I’m going home.” Only then did I appreciate how much better she was—from “death’s door” as it were—and we sent her home the next day. The wards demonstrate a phenomenon gone from American hospitals with their single and double rooms—patients helping each other. We had a 13 year old girl for 2 weeks, and she and the older women around her formed very sweet relationships, helping to get water, and just encouraging each others’ recovery.

I have been amusing my patients with Setswana, a little more each week. While a very kind young Motswana tutored me before my departure, I have struggled with how much to try to communicate in Setswana (the first language of most of my patients), or English (the official language of the country, which is familiar to most Batswana under 30, but quite variable in those who are older because schools were not universally available before the 1970s). I can say hello (dumela), please (ke kopa gore), thank you (ke a leboga), and basic greetings, and I have some medical vocabulary (madi for blood, mathata for problem, botlhoko for pain), but with only a few lessons and perhaps 20 hours to study, once I ask the question, what will I do with the answer? I think the main purpose of my attempts at Setswana is to express my respect for Botswana’s people and culture, and to offer an opening for them to share the ultimately personal and frightening symptoms that have brought them to medical care.

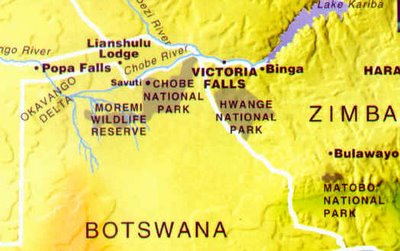

Last weekend I went with one of the others to Chobe National Park and Victoria Falls at the border of Zambia and Zimbabwe. Vic Falls is beautiful, but sad to see. The mighty Zambezie river which rushes over the rocks in Zambia to land in the gorge below is very dry, with a few small falls where a massive 1.7 km wall of water is meant to be. It is beautiful nonetheless, but one feels for the people and animals dependent on all that missing water.

The Chobe river in northern Botswana serves massive herds of elephants, hippos, antelope, and buffalo, and we got to see them in their natural glory.

This weekend I went to the edge of the Okavango Delta, where three of us stayed with a lovely Zimbabwean family who have worked in tourism all over Africa. They were extraordinary guides, and shared with us their local contingents of hippos, elephants, zebras, lions, giraffes, and a leopard with her little cub. Just breathtaking—you’ll have to see the pictures.

In a few days I return home. I have learned so many of the timeless lessons we all learn from travel. What is special about home, what is peculiar about home, and a tiny little bit about what it might be like to live another’s life…more on all this later.

Peace,

Carla

Sunday, November 20, 2005

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Touring Southern Africa

This weekend Carla will be traveling north to visit the famed Chobe Wildlife Reserve. A region rich in the famed flora and fauna of Africa. We all look forward to her report upon her return!

This weekend Carla will be traveling north to visit the famed Chobe Wildlife Reserve. A region rich in the famed flora and fauna of Africa. We all look forward to her report upon her return!One of the greatest natural wonders in Africa, the Falls of the Zambezi River, 5,400 feet wide, 320 feet deep. Named Victoria Falls after the English queen, by the explorer David Livingstone. The falls are not nearly this wet currently, as a result of 4 years of drought in the region. This stretch of the Zambezi River flows between the countries of Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Sunday, November 06, 2005

With another week gone, and a little more seasoned, medicine in Botswana is both more familiar and more extraordinary

November 6, 2005

Dear Friends and Family:

With another week gone, and a little more seasoned, medicine in Botswana is both more familiar and more extraordinary. The average age of my patients is mid-30s, with a few middle aged diabetics and elderly heart patients, and many young people admitted with HIV, meningitis, wasting syndrome, and coughs suspicious for TB, and often all of these. It’s not uncommon that I look at a patient, and only after looking at the chart do I appreciate how disease has aged them 10 or 20 years.

On the one hand, we don’t have all the tests we are used to back home (notably the CT scanner is broken and there are no MRIs; and the young patient we have with a bleed in her brain has to go to South Africa for further investigation since there is no place in the country to get an angiogram). On the other hand, we are finding we don’t need all of these tools for everyday diagnosis and treatment. Blood tests, ultrasounds, and other procedures we might otherwise do at home are passed in favor of empiric treatment for the most likely condition. Some of those tests really are redundant, and others simply confirm a suspicion. Sometimes we use them to decide between a number of different possibilities, but as often we are relatively certain before ordering the test.

One friend, John, before he left said that working here has made him more impressed with the amazing possibilities of trauma surgery, intensive care medicine, and the "good saves" of people with serious injuries and illnesses who we can return to normal lives. John also said his time here has also highlighted the ways that in the U.S. we sometimes lavish painful and expensive treatments on people who are obviously dying, and miss the opportunity to help patients and families come to terms with their deaths. I couldn’t agree more with both of John’s observations.

This practical approach to resource allocation is born of scarcity, but the fact that I can use my time and the hospital’s money doing what is possible instead of chasing rescue fantasies is reassuring. Our new medical student has observed that we don’t call "codes", as we do in the United States. Any patient not on hospice found pulseless in an American hospital will be subjected to a ritual of epinephrine, electric shocks, and chest compressions.

This is rarely helpful. In fact, outside of trauma situations in which a young person is bleeding and cardiac events in which a heart attack leads to a "shockable rhythm", patients who lose their pulse are usually quickly pronounced dead, subjected to another few days to weeks of intensive care only later to succumb, or are maintained in a "persistent vegetative state." This is not to say that we should not "do everything" for people with severe disabilities, but sometimes we prolong suffering without hope of improvement instead of prolonging meaningful life. Unlike at home, those with end-stage diseases are allowed to pass quietly.

There are frustrations: medications that would be useful, or even life-saving, which we are supposed to have, are mysteriously not in stock. Last week the laboratory computer system was down for 2 days, and lab results that take 1-2 hours at home, which can sometimes be had the same day at Marina, were held up in the queue. Supplies appear to back up at every level, with materials available from vendors, but not purchased; materials in the Ministry of Health’s central supplies, but not available at the flagship hospital, and items such as hand soap plentiful in the hospital stores but unavailable on the male medical ward…

On the weekend, we went away as we so often do, this time to the Khama Rhino Sanctuary in the center of the country, where we saw a few of Botswana’s remaining Rhinos (largely hunted to extinction for trophies and Chinese medicines), antelope of various kinds, wildebeests, hartebeests, zebras, and the "wild" painted dogs who are endangered.

Next week on to Victoria Falls and the Chobe Wildlife Reserve, where the largest groups of elephants and hippos in Botswana are to be found.

Peace,

Carla

Dear Friends and Family:

With another week gone, and a little more seasoned, medicine in Botswana is both more familiar and more extraordinary. The average age of my patients is mid-30s, with a few middle aged diabetics and elderly heart patients, and many young people admitted with HIV, meningitis, wasting syndrome, and coughs suspicious for TB, and often all of these. It’s not uncommon that I look at a patient, and only after looking at the chart do I appreciate how disease has aged them 10 or 20 years.

On the one hand, we don’t have all the tests we are used to back home (notably the CT scanner is broken and there are no MRIs; and the young patient we have with a bleed in her brain has to go to South Africa for further investigation since there is no place in the country to get an angiogram). On the other hand, we are finding we don’t need all of these tools for everyday diagnosis and treatment. Blood tests, ultrasounds, and other procedures we might otherwise do at home are passed in favor of empiric treatment for the most likely condition. Some of those tests really are redundant, and others simply confirm a suspicion. Sometimes we use them to decide between a number of different possibilities, but as often we are relatively certain before ordering the test.

One friend, John, before he left said that working here has made him more impressed with the amazing possibilities of trauma surgery, intensive care medicine, and the "good saves" of people with serious injuries and illnesses who we can return to normal lives. John also said his time here has also highlighted the ways that in the U.S. we sometimes lavish painful and expensive treatments on people who are obviously dying, and miss the opportunity to help patients and families come to terms with their deaths. I couldn’t agree more with both of John’s observations.

This practical approach to resource allocation is born of scarcity, but the fact that I can use my time and the hospital’s money doing what is possible instead of chasing rescue fantasies is reassuring. Our new medical student has observed that we don’t call "codes", as we do in the United States. Any patient not on hospice found pulseless in an American hospital will be subjected to a ritual of epinephrine, electric shocks, and chest compressions.

This is rarely helpful. In fact, outside of trauma situations in which a young person is bleeding and cardiac events in which a heart attack leads to a "shockable rhythm", patients who lose their pulse are usually quickly pronounced dead, subjected to another few days to weeks of intensive care only later to succumb, or are maintained in a "persistent vegetative state." This is not to say that we should not "do everything" for people with severe disabilities, but sometimes we prolong suffering without hope of improvement instead of prolonging meaningful life. Unlike at home, those with end-stage diseases are allowed to pass quietly.

There are frustrations: medications that would be useful, or even life-saving, which we are supposed to have, are mysteriously not in stock. Last week the laboratory computer system was down for 2 days, and lab results that take 1-2 hours at home, which can sometimes be had the same day at Marina, were held up in the queue. Supplies appear to back up at every level, with materials available from vendors, but not purchased; materials in the Ministry of Health’s central supplies, but not available at the flagship hospital, and items such as hand soap plentiful in the hospital stores but unavailable on the male medical ward…

On the weekend, we went away as we so often do, this time to the Khama Rhino Sanctuary in the center of the country, where we saw a few of Botswana’s remaining Rhinos (largely hunted to extinction for trophies and Chinese medicines), antelope of various kinds, wildebeests, hartebeests, zebras, and the "wild" painted dogs who are endangered.

Next week on to Victoria Falls and the Chobe Wildlife Reserve, where the largest groups of elephants and hippos in Botswana are to be found.

Peace,

Carla

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)